Agricultural machinery testing, modus operandi

From January 1888 onwards, the agricultural machinery testing station carried out tests on agricultural equipment in order to provide farmers with reliable and verified information on the capabilities of existing equipment. Rigour and method are at the heart of this work.

A little history

Professor Ringelmann (1861-1931) presided over the destiny of the machinery testing station (SEMA) of the Ministry of Agriculture for forty-three years. He endeavoured to progressively extend the fields of activity of this organisation in order to meet the new needs arising from the progress of agricultural machinery. This is why he devoted a large part of his time to experiments intended to provide controlled indications on the best conditions for the use of various agricultural equipment.

He endeavoured to respond to the numerous enquiries he received from farmers and manufacturers in order to help achieve rational equipment for French agriculture. In 1920, he created a section for the application of agricultural mechanics with the aim of training engineers and technicians specialised in agricultural machinery.

SEMA was set up in temporary premises in rue Jenner in Paris. In 1913, this station was transferred to another address in Paris, avenue de St-Mandé, where it operated until the French National Centre for the Study and Experiment of Agricultural Machinery (CNEEMA) was established in 1955.

The tests carried out

A large part of the test reports produced by SEMA between 1888 and 1935 have been preserved by the organisations that succeeded it, CNEEMA and then the French National Centre of Agricultural Machinery, Rural Engineering, Water and Forestry (Cemagref).

These documents, handwritten until the end of the 1920s, allow us to rediscover the agricultural equipment available in France in the first third of the 20th century and to learn about its physical characteristics, strengths and weaknesses.

From the cream separator to the tractor, via the excavator or the seed planter, all these objects were tested in order to recommend, or not, their use and the optimal conditions of use.

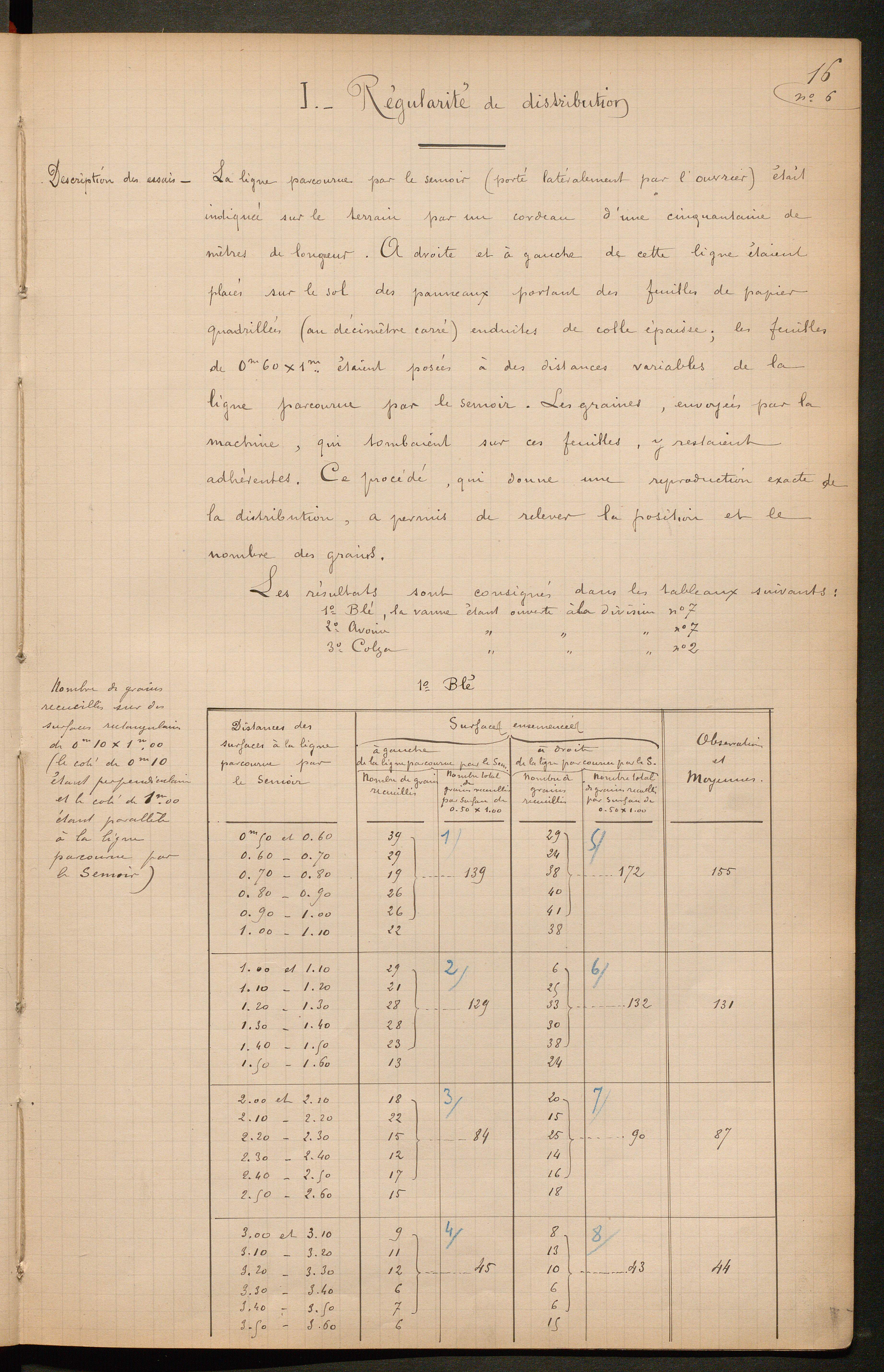

Like today's laboratory notebooks, the test reports were transcribed in a uniform manner:

- the name of the object and its price,

- the name of the manufacturer or dealer

- its general description,

- the test itself with the aims and criteria of the experiments, the conditions and the measurements carried out,

- the conclusion on the quality of the object, its limitations or strengths.

"The testing of machines, and in particular of agricultural machines, is a delicate and complex task of which we can only give a general overview here:

A test must be as complete as possible, so that the discussion of its results can determine the value of the machine under consideration; it is therefore necessary to take into account:

- The quantity and quality of practical work performed under various operating conditions;

- The amount of energy, or mechanical work, required for operation;

- The probable duration of the machine, based on an examination of the construction itself: like the nature of the materials used, the arrangement of the various components and the adjustment of the various parts.

These three main data make it possible to evaluate the cost price of the work of the machine in question. (Ringelmann, Mechanics at the 1900 exhibition (La mécanique à l'exposition de 1900), 1901, pp. 211-224

Description of the test conditions for the "La trouvaille" broadcast seeder, presented to SEMA by its inventor Mr. Duncan in October 1889.

This document is a good example of the nature of the criteria used and the extreme care taken to maximise the objectivity of the experimental conditions and to take into account as many criteria as possible.

Text written by Pascale Hénaut (INRAE-DipSO).

Thanks to Camille Cédra, retired engineer from Cemagref, for his proofreading.

How to cite: Agate Focus: Agricultural machinery testing, modus operandi, Pascale Hénaut (INRAE-DipSO), march 2023, https://agate.inrae.fr/agate/en/content/highlights