Charles Bonnet's fatherless aphids

In 1745, Charles Bonnet describes the multiple experiments (carried out) under controlled conditions that enabled him to demonstrate the existence of asexual reproduction in aphids. Making the data available and describing the protocol to make it reproducible are still at the heart of the scientific approach today.

A young Genevan, inventor of insectology

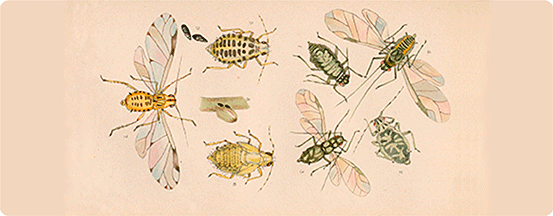

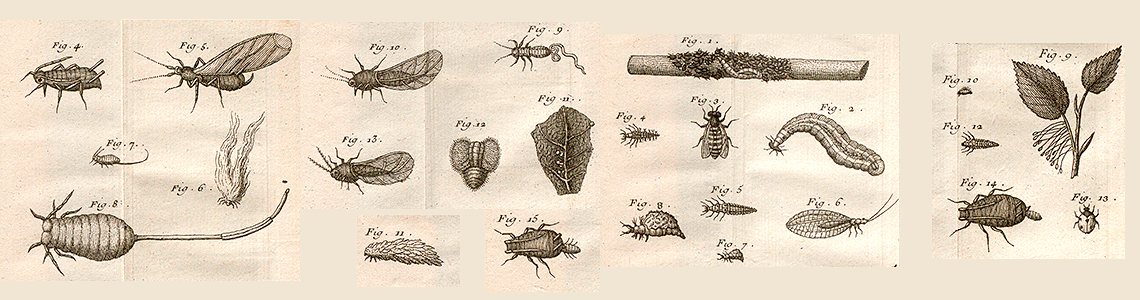

Although the study of insects existed long before Charles Bonnet (1720-1793), he coined the term insectology in the preface to his work “Traité d'insectologie” (Treatise on Insectology). The science of insects had not yet been given a specific name, unlike the study of plants (botany) or stones (lithology, later mineralogy). The term was replaced by entomology in the 19th century.

A passionate young man

At the age of 17, Charles Bonnet writes to René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur. Réaumur, director of the French Académie des Sciences in Paris, had just published "Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des insectes" (Essays for use in the history of insects). Bonnet presents him with an essay on the behaviour of a caterpillar that weaves a silk thread to find its way back to its nest. It is the beginning of a correspondence between the brilliant and well-known scientist and the enthusiastic young man.

Réaumur suggests he should look into what appears to be asexual reproduction in aphids. Réaumur had not yet succeeded in carrying out the experiment that would demonstrate this. The idea was "to take an aphid as it leaves its mother's womb and to rear it in such a way that it cannot have any contact with any insect of its kind".

Experimentation

Charles Bonnet recounts his first conclusive experiment with a black bean aphid, which he removes at birth and places in an experimental device isolating the insect from all contact with its fellow aphids. He observes the insect hourly with a magnifying glass to study its behaviour and development. He describes the aphid's moults and its appearance at the various stages.

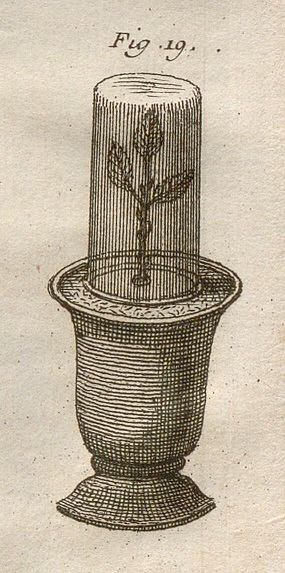

Fig. 16: "earthen jar" – Fig. 17: "glass bottle, intended to be placed in the earthen jar" – Fig. 18: the "bottle, placed in the jar, is covered up to the neck by the earth with which the jar has been filled. Above the neck rises a small stem bearing leaves on which a budding aphid has been placed".

Fig. 19: add to the previous device, "a glass vase or powder jar, under which have been enclosed the leaves which are to supply the nourishing juices to the aphid condemned to live in perfect solitude. The edges of the powder jar are pressed neatly against the earth and covered with it".

It is after a month of observations, on 1 June 1740, at around 7 o'clock in the evening that Charles Bonnet "saw with great satisfaction that it had given birth". Over (the following) 21 days, "the lady aphid" will give birth to 95 young.

He sends his results to Réaumur, who asks him to repeat the experiment, which was done the following year with 2 black bean aphids, isolated and "reared in solitude" using the same protocol.

A 3rd set of experiments subsequently focusses on elder aphids. The aim is to ensure that this property of procreating without the need for mating is maintained from generation to generation. His uncle, Abraham Trembley, also a naturalist, suggests to him that one mating might suffice for several generations. Bonnet therefore extends his experiments to 5 and then 9 generations of elder aphids "reared in solitude", all of which procreate without mating.

...as an element of proof

"Today's observer of nature is not content to carry out experiments that will help him discover the truth; he examines it with such certainty that it dispels even the slightest doubt. He does not allow the faintest suspicion, the smallest cloud to weaken its radiance" (Treatise, volume 1, p.75).

Charles Bonnet describes the details of the experiment, its repetitions and the material conditions applied. (p. 208-210) He describes both the failures and the successes met with.

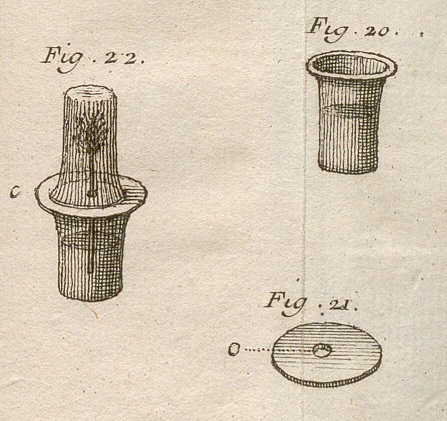

Fig. 20: "glass powder jar half-filled with water" – Fig. 21: "a round piece of cardboard C, with a hole O in the middle, which shall be placed on the powder jar in figure 20" – Figure 22: "this powder jar covered with its cardboard C, through the hole of which passes a stalk of plantain, the spike of which is enclosed in another glass powder jar, the opening of which fits exactly over the cardboard C."

Everything is placed in the earthen pot as for device 1.

He provides the reader with tables showing the data collected during his observations (e.g. p. 104).

The aim of each of these elements is to establish proof of a biological mechanism. Repeated observations, under controlled conditions, are made on several aphid species to rule out any particularities. In so doing, he moves from the particular to the general. Beyond the mere observation, Charles Bonnet develops well-argued proof of a mechanism that is stable over time (repetition and seasonality of experiments) and common to many aphid species.

And nowadays at INRAE?

INRAE is a signatory to the French National Charter for Research Integrity.

One of the principles of integrity formulated is that of the reliability of research work: it is imperative to describe research protocols in order to ensure the reproducibility of scientific experiments. The raw results and the analysis of the results must be preserved. They are destined to be disseminated to the scientific community and the general public.

In this, our researchers are the worthy heirs of Charles Bonnet.

Bibliographic sources

Bonnet, C. (1745). Traité d'insectologie ou Observations sur les pucerons. Première partie. (Treatise on Insectology. First Volume. In French). Éditions Durand (Paris), 288 p.

Bonnet, C. (1745). Traité d'insectologie ou Observations sur les pucerons. Seconde partie. (Treatise on Insectology. Second Volume. In French). Éditions Durand (Paris), 232 p.

Vos, A. (2012). Charles Bonnet, géant de la nature. (Charles Bonnet, giant of nature. In French). Campus, le magazine scientifique de l'UNIGE, n°109, juin-septembre 2012. https://www.unige.ch/campus/numeros/109/tetechercheuse/

Les pucerons, objets scientifiques : l’énigme de la reproduction. (Aphids as scientific objects: the enigma of reproduction. In French). Encyclop'Aphid : l'encyclopédie des pucerons, https://encyclopedie-pucerons.hub.inrae.fr/pucerons-et-recherche/les-debuts-de-l-aphidologie/reproduction

Sigrist, R. (2001). L'expérimentation comme rhétorique de la preuve : L'exemple du Traité d'insectologie de Charles Bonnet. (Experimentation as the rhetoric of proof: the example of Charles Bonnet's Treatise on Insectology. In French). Revue d'histoire des sciences, 54-4, p. 419-449. https://www.persee.fr/doc/rhs_0151-4105_2001_num_54_4_2133

Text written by Pascale Hénaut (INRAE-DipSO).

How to cite: Focus Agate: Charles Bonnet's fatherless aphids, Pascale Hénaut (INRAE-DipSO), April 2024. https://agate.inrae.fr/agate/en/content/focus